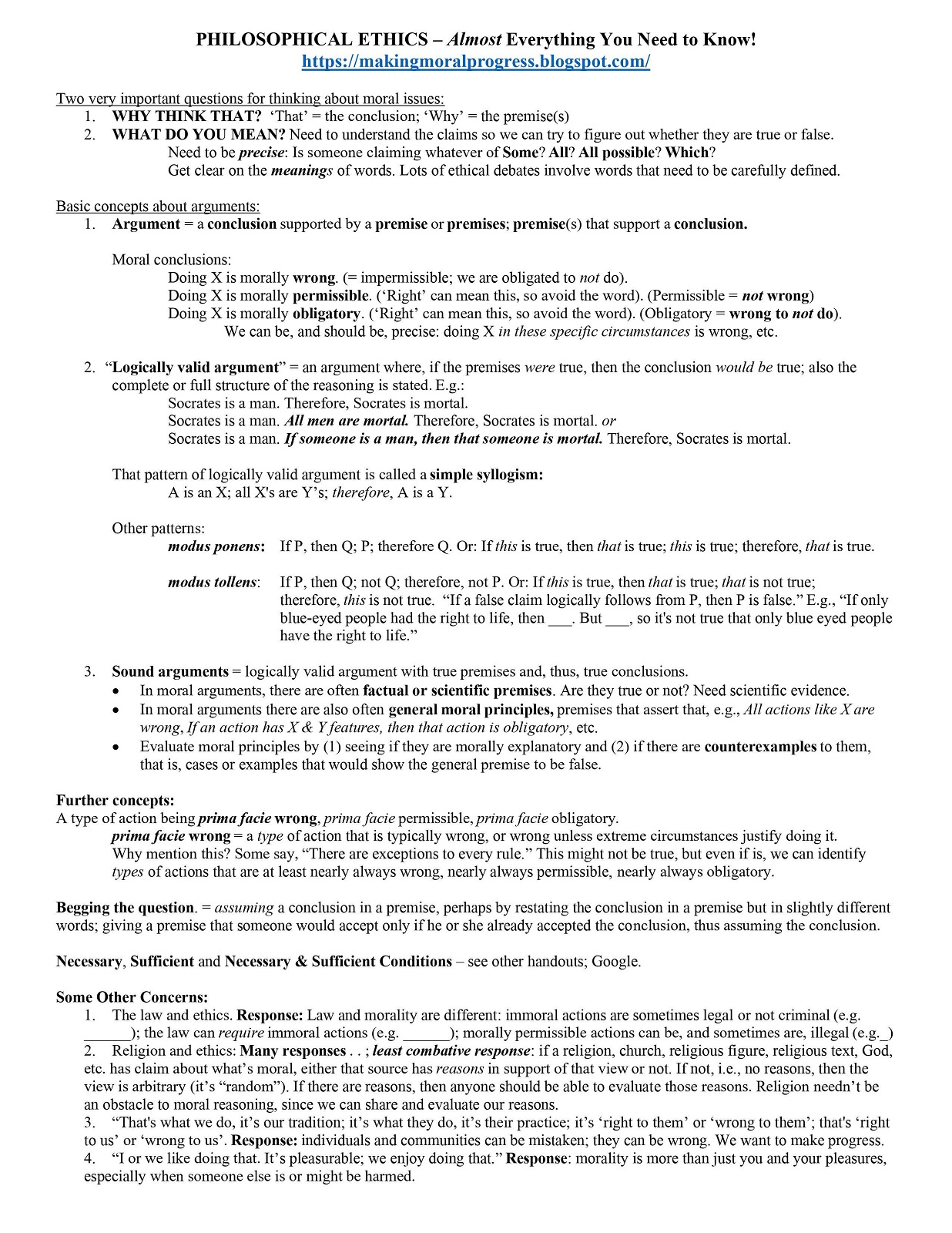

PHILOSOPHICAL ETHICS – Almost Everything You Need to Know! https://makingmoralprogress.blogspot.com/

Two very important questions for thinking about moral issues:

1. WHY THINK THAT? ‘That’ = the conclusion;

‘Why’ = the premise(s)

2. WHAT DO YOU MEAN? Need to

understand the claims so we can try to figure out whether they are true or

false.

Need to be precise: Is someone claiming

whatever of Some? All? All possible? Which?

Get clear on the meanings of words. Lots of ethical debates involve words that need to be

carefully defined.

Basic concepts about arguments:

1. Argument = a conclusion supported by a premise or premises; premise(s)

that support a conclusion.

Moral

conclusions:

Doing X is morally

wrong. (= impermissible; we are

obligated to not do).

Doing X is

morally permissible. (‘Right’ can

mean this, so avoid the word). (Permissible = not wrong)

Doing X is

morally obligatory. (‘Right’ can

mean this, so avoid the word). (Obligatory = wrong to not do).

We can be, and

should be, precise: doing X in these

specific circumstances is wrong, etc.

2. “Logically valid argument” = an argument where, if the

premises were true, then the conclusion would be true; also the

complete or full structure of the reasoning is stated. E.g.:

Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Socrates

is a man. All men are mortal. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. or

Socrates is a man. If someone is a man, then that someone is mortal. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

That pattern of logically valid argument is

called a simple syllogism:

A is an X; all X's are Y’s; therefore, A is a Y.

Other patterns:

modus ponens: If P, then Q; P;

therefore Q. Or: If this is true, then that is true; this is

true; therefore, that is true.

modus tollens: If P, then Q; not Q; therefore, not P. Or: If this is true, then that is true; that is

not true; therefore, this is not true. “If a false claim logically follows from P, then P is false.” E.g.,

“If only blue-eyed people had the right to life, then ___. But ___, so it's not

true that only blue eyed people have the right to life.”

3. Sound arguments = logically valid argument with true premises and, thus, true

conclusions.

·

In moral

arguments, there are often factual or scientific premises. Are they true

or not? Need scientific evidence.

·

In moral

arguments there are also often general moral

principles, premises that assert that, e.g., All actions like X are

wrong, If an action has X & Y features, then that action is obligatory,

etc.

·

Evaluate moral

principles by (1) seeing if they are morally explanatory and (2) if there are counterexamples to

them, that is, cases or examples that would show the general premise to be

false.

Further concepts:

A type of action being prima facie wrong, prima

facie permissible, prima facie obligatory.

prima facie wrong = a type of action that

is typically wrong, or wrong unless extreme circumstances justify doing it.

Why mention this? Some say, “There are exceptions to every rule.”

This might not be true, but even if is, we can identify types of actions that are at least nearly always wrong, nearly

always permissible, nearly always obligatory.

Begging the question. = assuming a conclusion in a premise, perhaps

by restating the conclusion in a premise but in slightly different words;

giving a premise that someone would accept only if he or she already accepted

the conclusion, thus assuming the conclusion.

Necessary,

Sufficient and Necessary & Sufficient Conditions – see other handouts; Google.

Some Other Concerns:

1. The law and ethics. Response: Law and morality are

different: immoral actions are sometimes legal or not criminal (e.g. ______);

the law can require immoral actions (e.g. ______); morally permissible

actions can be, and sometimes are, illegal (e.g._)

2. Religion and ethics: Many responses . . ; least

combative response: if a religion, church, religious figure, religious

text, God, etc. has claim about what’s moral, either that source has reasons in

support of that view or not. If not, i.e., no reasons, then the view is

arbitrary (it’s “random”). If there are reasons, then anyone should be able to

evaluate those reasons. Religion needn’t be an obstacle to moral reasoning,

since we can share and evaluate our reasons.

3. “That's what we do, it’s our tradition; it’s what they do, it’s

their practice; it’s ‘right to them’ or ‘wrong to them’; that's ‘right to us’ or

‘wrong to us’. Response: individuals and communities can be mistaken;

they can be wrong. We want to make progress.

4. “I or we like doing that. It’s pleasurable; we enjoy doing that.” Response:

morality is more than just you and your pleasures, especially when someone else

is or might be harmed.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.